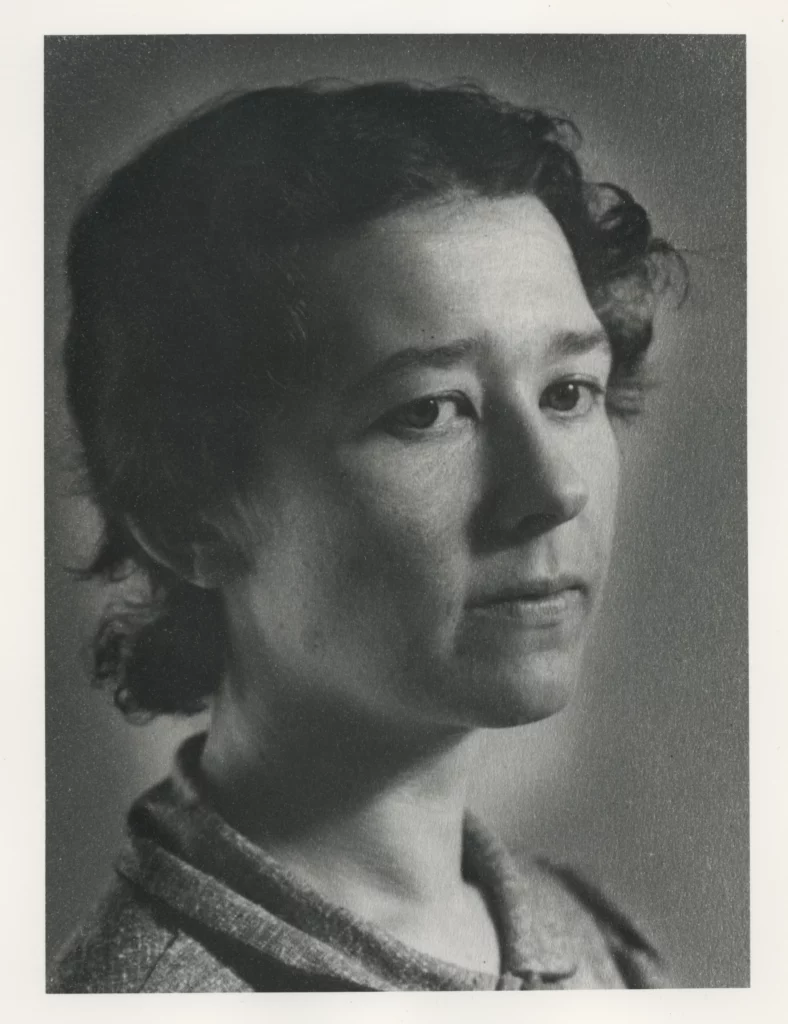

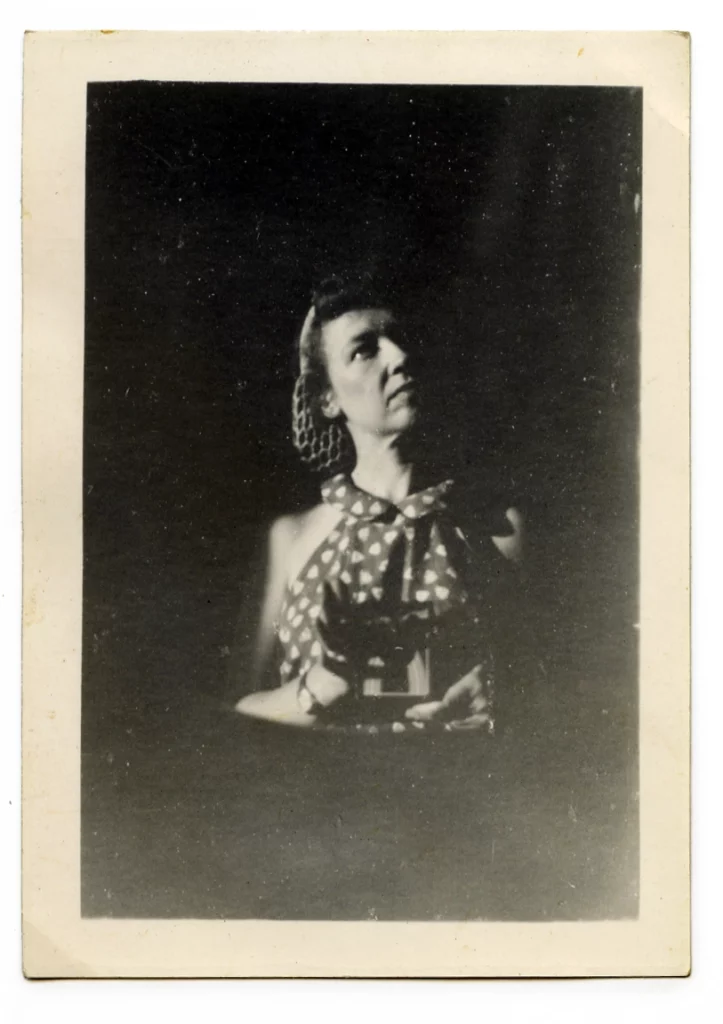

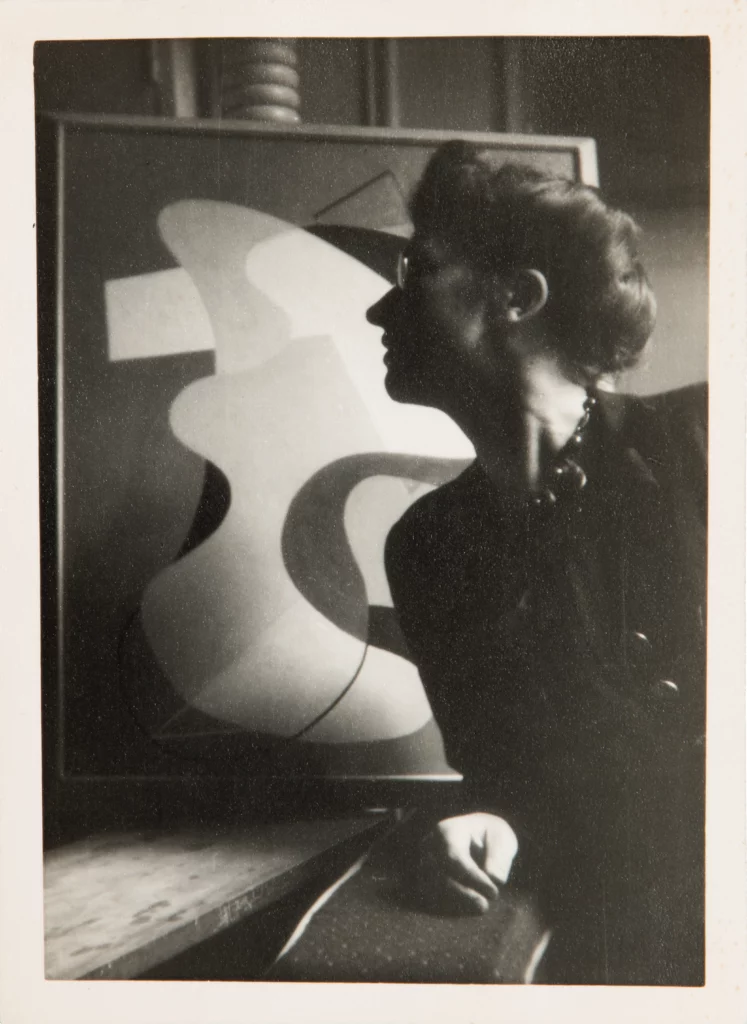

Alice Trumbull Mason Chronology 1904-1971

“We look for nothing mystical or dreamlike but in the magic in the work itself. Abstract art demands an awareness of the intrinsic use of materials and fuller employment of these means which build a new imaginative world by using them for their own potential worth."

1904

Alice Trumbull is born to Anne Leavenworth Train and William Trumbull on November 16th in Litchfield, Connecticut. She is the fifth of six children and asserts herself as a natural rebel and leader at a young age. Her older sister Margaret Jennings later recalled that her younger sister taught herself how to read by the age of five, and that “what Alice wanted to do, you know that the family did it.”

1920-1922

Trumbull travels with her family to Italy. They live outside Florence in Fiesole, where she begins her studies in Latin and Greek. They later move to Rome, where she attends the British Academy of Arts in Rome.

1923

Trumbull and her parents move to West 116th Street in New York City, where she enrolls in Charles W. Hawthorne’s classes at the National Academy of Design

1925-1926

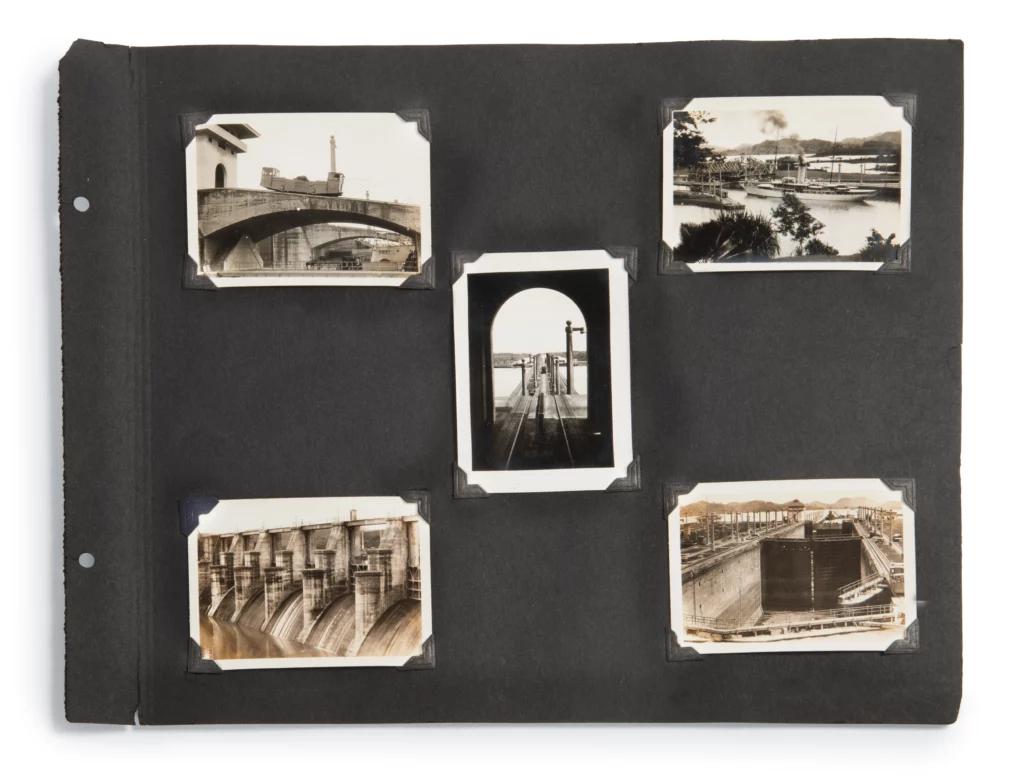

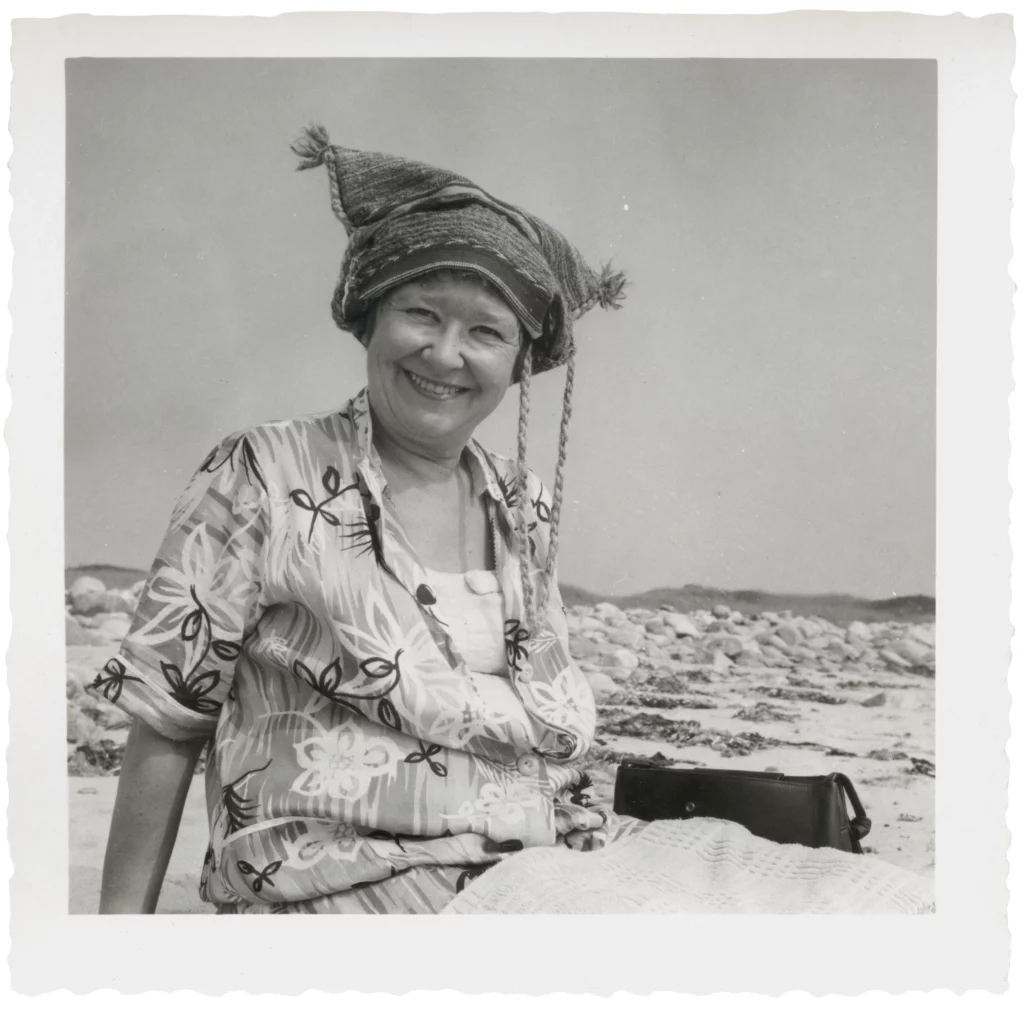

Trumbull travels with her aunt Anne Trumbull on a world cruise from November 25, 1925, to April 6, 1926. The cruise begins in New York and includes stops in Cuba, Panama, California, Hawaii, Japan, China, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Malaysia, India, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Egypt, Palestine, Italy, the French Riviera, and Spain. While aboard the ship, she attends lectures on the history of each destination. She maintains a detailed journal of her travels and illustrates it with photographs.

1927

Trumbull returns to her artistic training with Hawthorne at the National Academy of Design in New York. There she befriends artists Ilya Bolotowsky and Esphyr Slobodkina.

With her mother she spends the summer in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where she continues to study with Hawthorne.

1928

During the summer, Trumbull attends the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire. During the fall and early winter, she studies under Arshile Gorky at the Grand Central School of Art in New York City. “He really opened my eyes to abstract painting,” she would say of Gorky years later, even though, “he himself wasn’t very strongly abstract at that time.”

She travels with her sister Margaret Jennings to Italy and Greece to study her favorite periods in art history, including Archaic Greek, Byzantine, and Italian primitivism. Trumbull meets Warwood E. Mason during their voyage aboard the Coeur d’Alene, where he is second mate. They meet again in Greece and fall in love.

1929

In correspondence with her younger sister, Edith, Trumbull writes that she has fallen for Warwood but that she wishes to end the relationship because of her commitment to her “free life-, [her] alone-ness and lovely work which is impossible for another to share.”

Back in New York, she obtains a studio and begins painting her first abstractions, inspired by her recent travels. She spends the summer with her mother in Nova Scotia and corresponds frequently with Warwood while he is at sea.

In a letter to Warwood, Trumbull describes her newfound dedication to living as an artist: “I know that the whole of life is declaring and manifesting good—is proving what is true, there’s no use saying it. I am doing it. And my works show forth, manifest, prove—because the foundation is unity. And because I know I am whole.”

1930

In January, her mother, a devoted Christian Scientist, takes ill and refuses medical intervention due to her beliefs. She passes away shortly thereafter. Her mother’s death has a profound impact on her view of religion and spirituality, which she conveys in a letter to Warwood: “Mysticism became too shallow a thing and after a period of rather physical regard for trees, which followed the intense mysticism, I turned to a keen religious asceticism.”

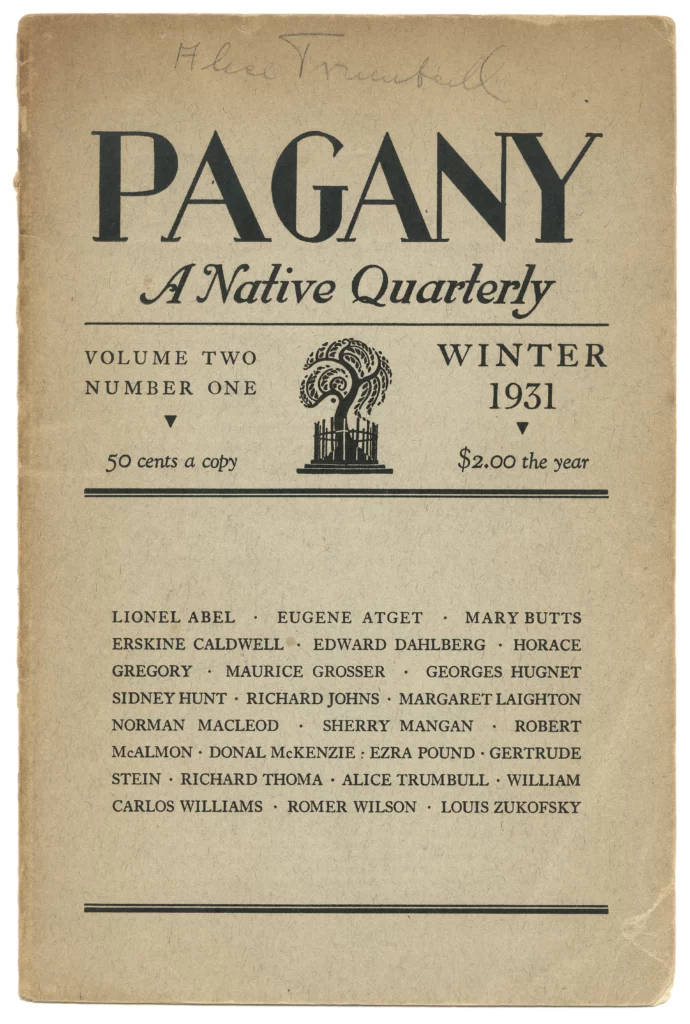

Trumbull corresponds with William Carlos Williams about her poetry. He offers edits for her poem “Trees” and, after changes are made, he submits it to the journal Pagany for publication.

In December, she marries Warwood at the municipal office at City Hall in New York. She takes her husband’s name. Her father is very pleased with the marriage and declares that Warwood is his favorite of all of his sons-in-law.

1931

Alice Trumbull Mason and Warwood Mason move to Grove Street in the West Village on March 23. In April, she learns she is pregnant with their daughter, Emily.

Alice Trumbull Mason corresponds with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in France. Stein reads her poetry and encourages her to publish.

Pagany publishes Mason’s poem “Trees” in its Winter 1931 issue, alongside the poetry of William Carlos Williams and Gertrude Stein.

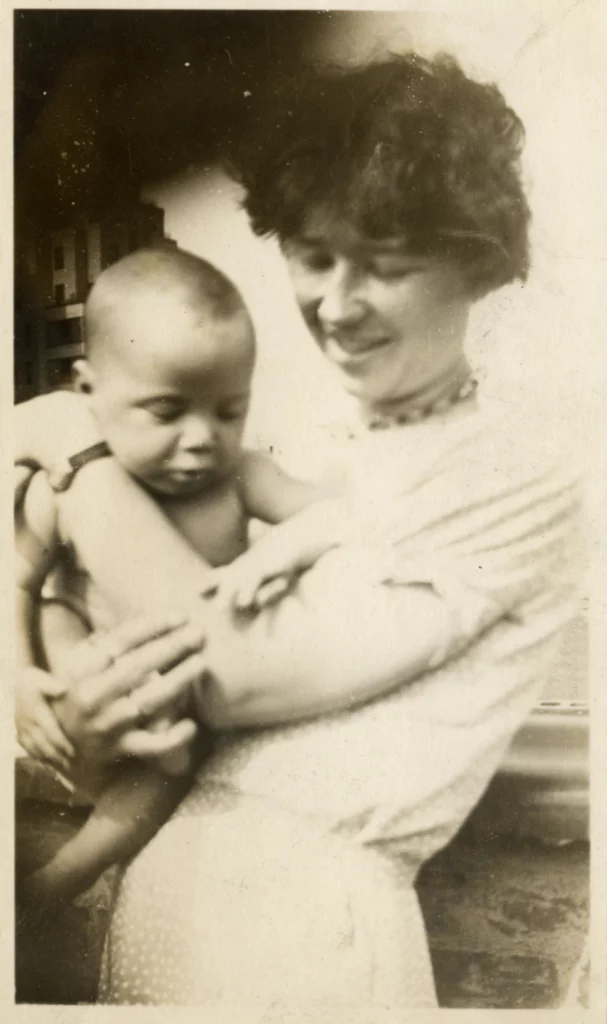

1932

On January 12, while Warwood is at sea, she travels alone by subway to Sydenham Hospital in Harlem, where she gives birth to their daughter, Emily. She recovers with her sister Margaret in White Plains, New York.

She writes to Warwood describing the twenty-hour birth: “It was a tremendous experience—and I wouldn’t have missed it for anything in the world. In fact I really enjoyed it!”

In the fall, while Warwood is away, she moves the family to a basement apartment at 83 Horatio Street in the West Village.

1933

In January her father dies.

On November 16, her birthday, Mason gives birth to her second child, Jonathan. Jonathan, who goes by Jo, is born with a cleft lip and a heart murmur, making the first year of his life very stressful for Mason. Warwood is away for most of this year, so she cares for their two children alone. Money is scarce and she keeps very detailed records of her spending.

1934

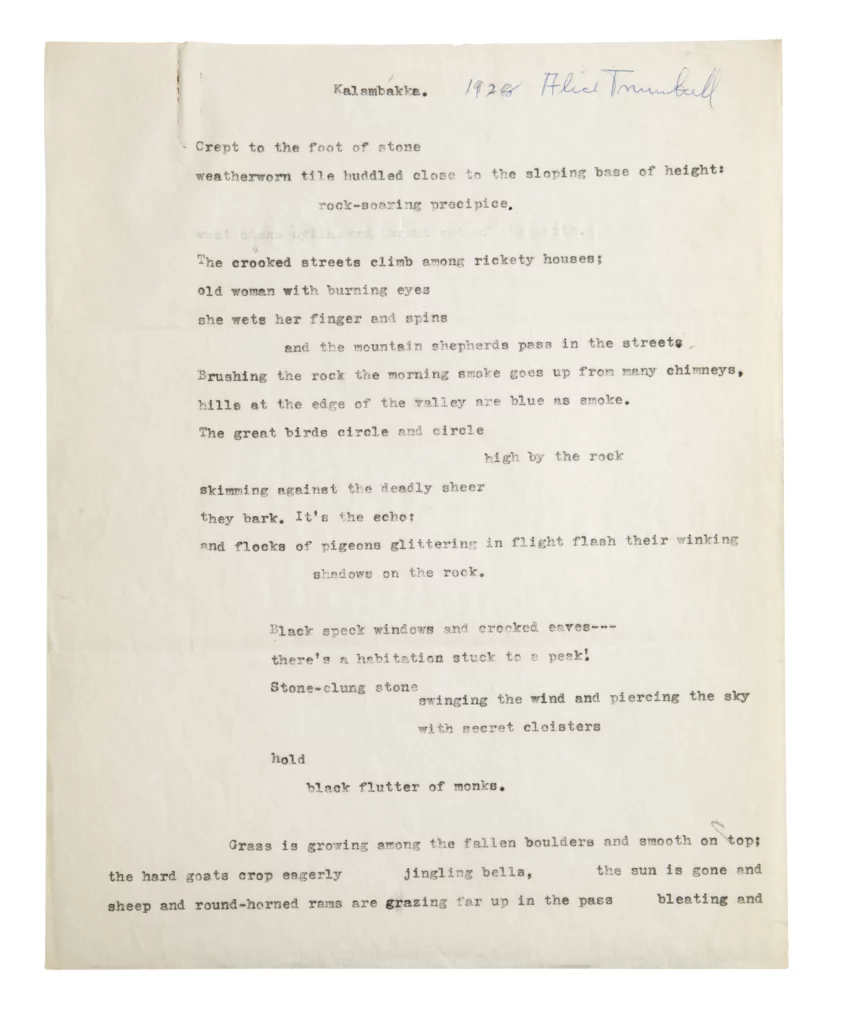

In June Mason’s poem “Kalambakka” is published in the American Poetry Journal.

Over the summer, the family moves to the first floor of 83 Horatio Street. In the fall, with the children enrolled in nursery school, she begins painting regularly again.

1935

In September, Mason participates in the Washington Square Art Show, where she is the only one of over 400 artists to display abstract work. During the run of the show, she meets the abstract sculptor Ibram Lassaw.

Years later, Lassaw would recall running into Mason with her work on the steps of the Judson Memorial Church: “Suddenly I saw her paintings and oh my god, here’s a real artist! … [T]here were so few abstract artists in those days, it was a rare thing.”

Mason, Lassaw, Bolotowsky, Slobodkina, and others begin to hold meetings that will give rise to the group American Abstract Artists (AAA), which will officially be founded in 1936.

1936

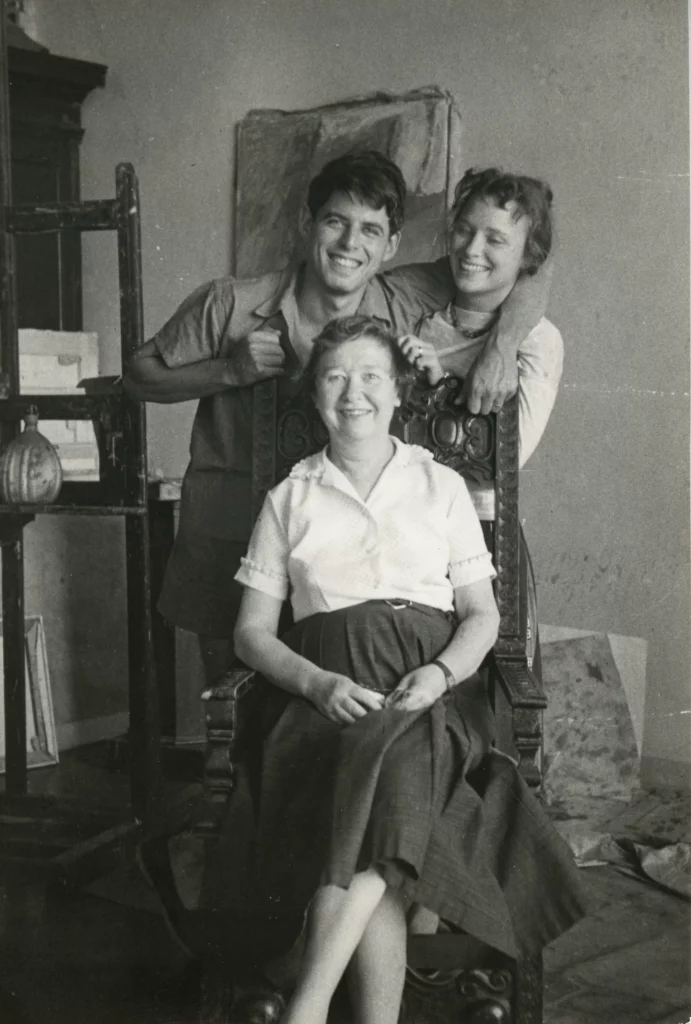

Mason becomes romantically involved with Ibram Lassaw. During the spring, Lassaw and Mason take Emily and Jo on day trips to Candlewood Lake in Connecticut, a tradition that would continue through 1941.

In the fall, the family moves to Knickerbocker Village on the Lower East Side. Mason can afford to hire someone to help with the home and children while she paints and her husband is away.

1937

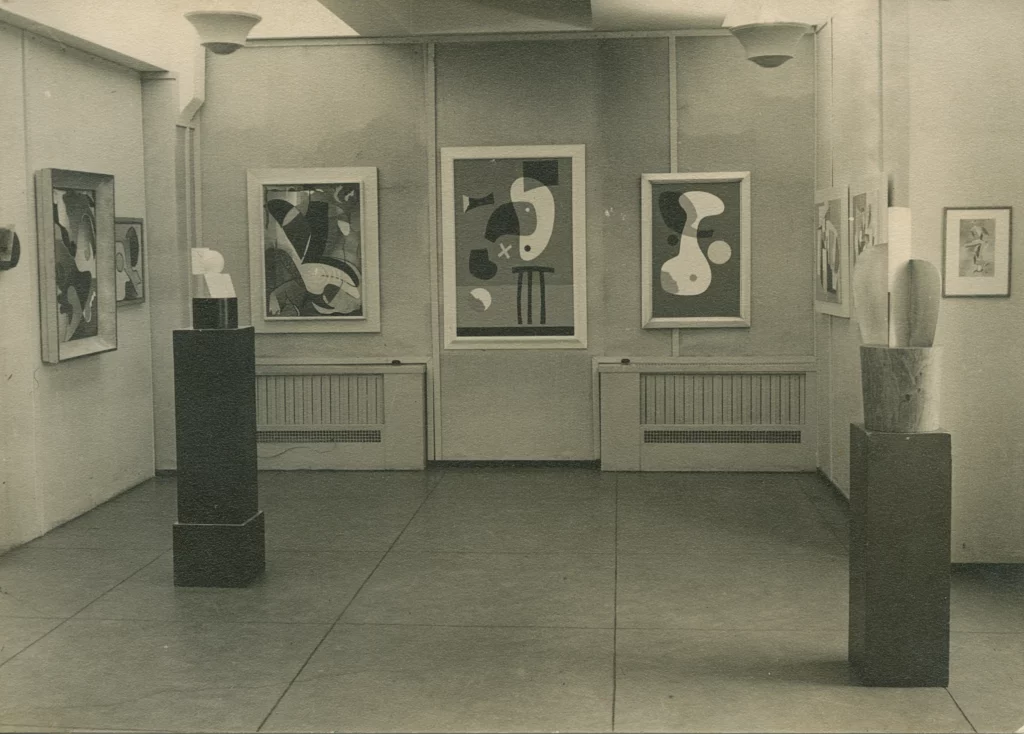

In March, she shows work with the AAA at Squibb Gallery on 58th Street and Fifth Avenue for the first time.

1938-1939

Mason writes “Concerning Plastic Significance” for the AAA’s Squibb Gallery exhibition. In this essay, she describes abstraction as “the true realism.”

The Whitney Museum of American Art’s Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting opens November 2 and runs through December 11, 1938. Mason participates with A Drawing in Oil Paint (1937).

She serves as AAA treasurer in 1939.

1940

Mason pickets the Museum of Modern Art along with most current members of the AAA, including Bolotowsky, Lassaw, Slobodkina, Josef Albers, Gertrude Greene, and Carl Holty, to protest the exclusion of American abstract artists from the exhibitions Art in Our Time; Cubism and Abstract Art; and Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism.

Mason begins serving as AAA secretary and will hold the position from 1940 to 1945.

Hilla Rebay, director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (then known as the Museum of Non-Objective Painting), takes an interest in the work of young non-objective artists, including Mason. Rebay grants Mason a stipend of fifteen dollars per month to purchase art materials. In exchange, Mason is required to attend Rebay’s monthly critiques. In the years to come, Rebay will buy two of Mason’s paintings for the museum’s collection.

1941

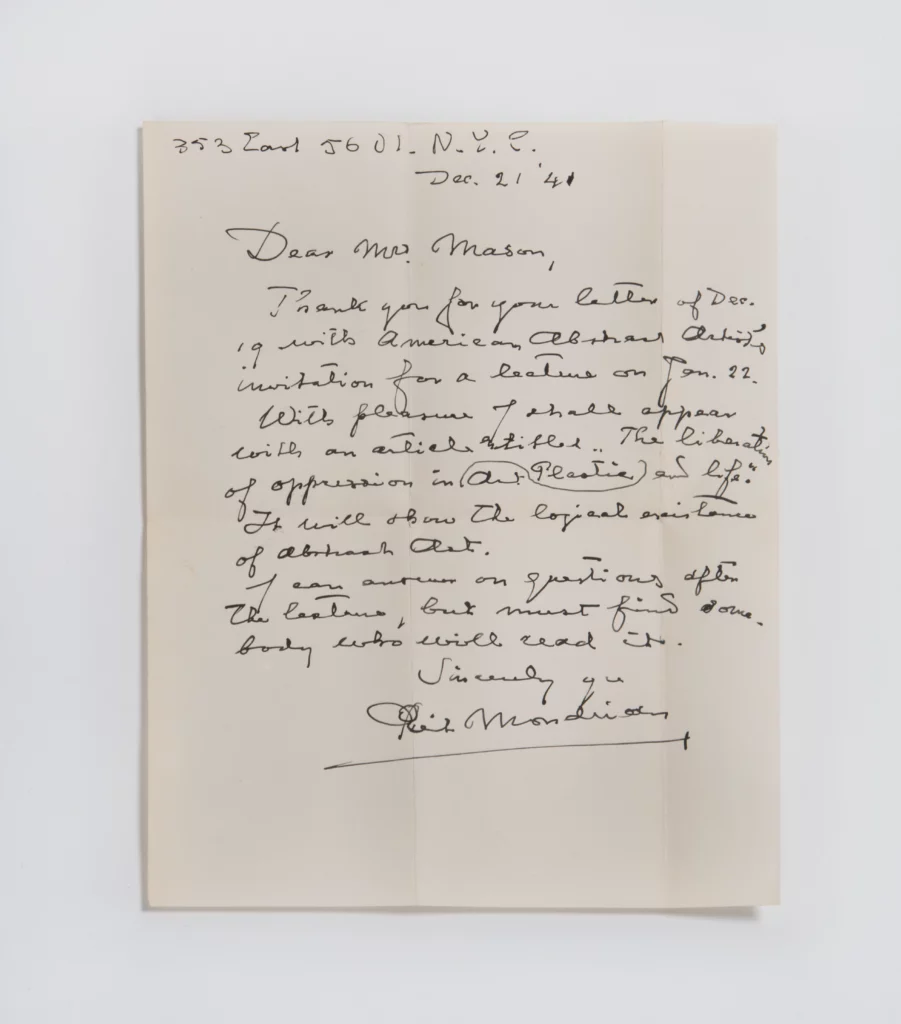

On behalf of the AAA, Mason invites Piet Mondrian to give a lecture in January (1942). He accepts: “With pleasure I shall appear with an article titled ‘The Liberation of Oppression in Plastic Art and Life.’” Mason and Mondrian would correspond regularly until his death in 1944.

1942

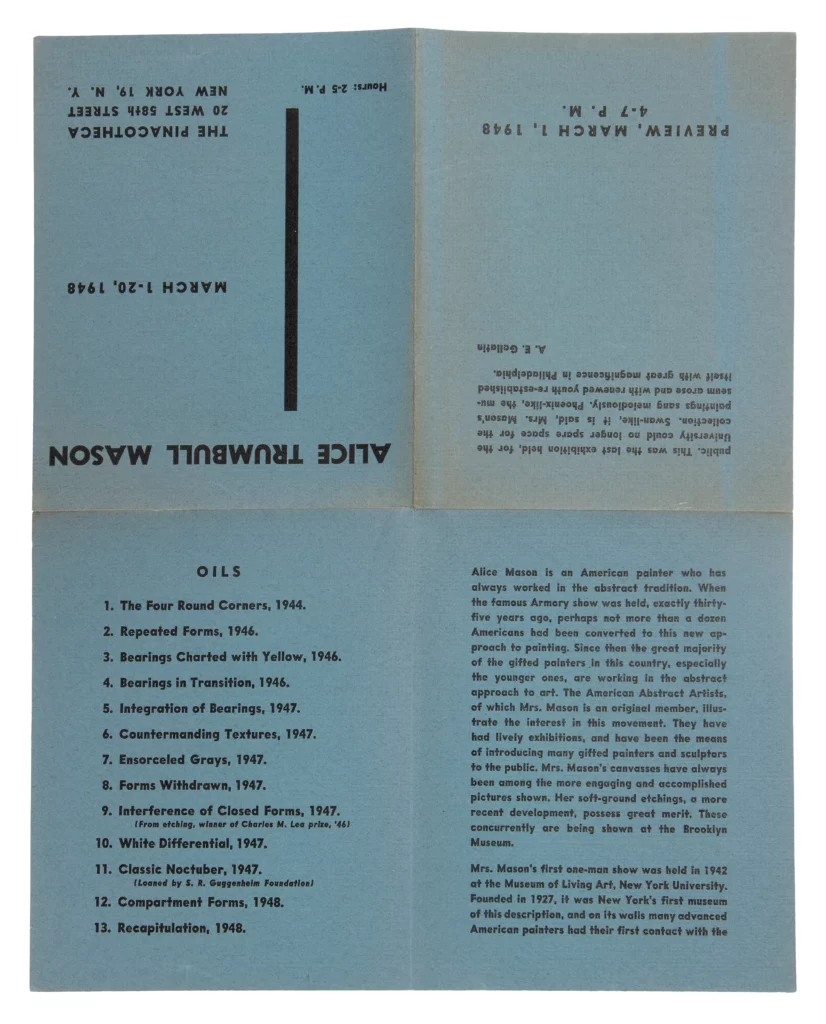

In November, Mason has her first solo show at the Museum of Living Art on Washington Square, sponsored by A. E. Gallatin.

In the fall, Warwood is diagnosed with phlebitis. He is transferred to a permanent desk job as assistant port captain in Newark. The family moves to 334 West 85th Street on the Upper West Side (they enjoyed being close to Riverside Drive). For the first time in their relationship, Mason and Warwood live together as a family year-round.

Mason ends her romantic relationship with Ibram Lassaw, but they remain good friends for the rest of their lives.

1943

Mason joins the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors and serves as its secretary from 1943 to 1944.

Her daughter, Emily, is at camp, and they correspond often. Mason is proud of the young lady Emily is becoming and appreciates how much they share in common: art, literature, and a love of nature.

In May, Mason participates in a juried group show at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery. She writes to Lassaw, “I saw Peggy’s show this afternoon. It is not bad, but heavily surrealistic. Included are you, Reinhardt, Pereira, Geist, Slobodkina, Bolotowsky, me!”

1944

Mason joins Atelier 17, Stanley William Hayter’s avant-garde printmaking studio.

She moves to her new studio at East 119th Street and Lexington Avenue.

In a letter to Hilla Rebay, Mason writes, “The Museum of Non-Objective Painting has the honor of being the only one to show new, unknown, and experimental work consistently.”

1945

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum acquires Mason’s painting Emergent Form (1945).

She visits the Kandinsky memorial exhibition and afterward writes to Rebay, who organized it, describing it as “an imposing presentation of that great artist’s work … a real experience for a great number of us to have this opportunity to study so fully his life’s expression.”

1946

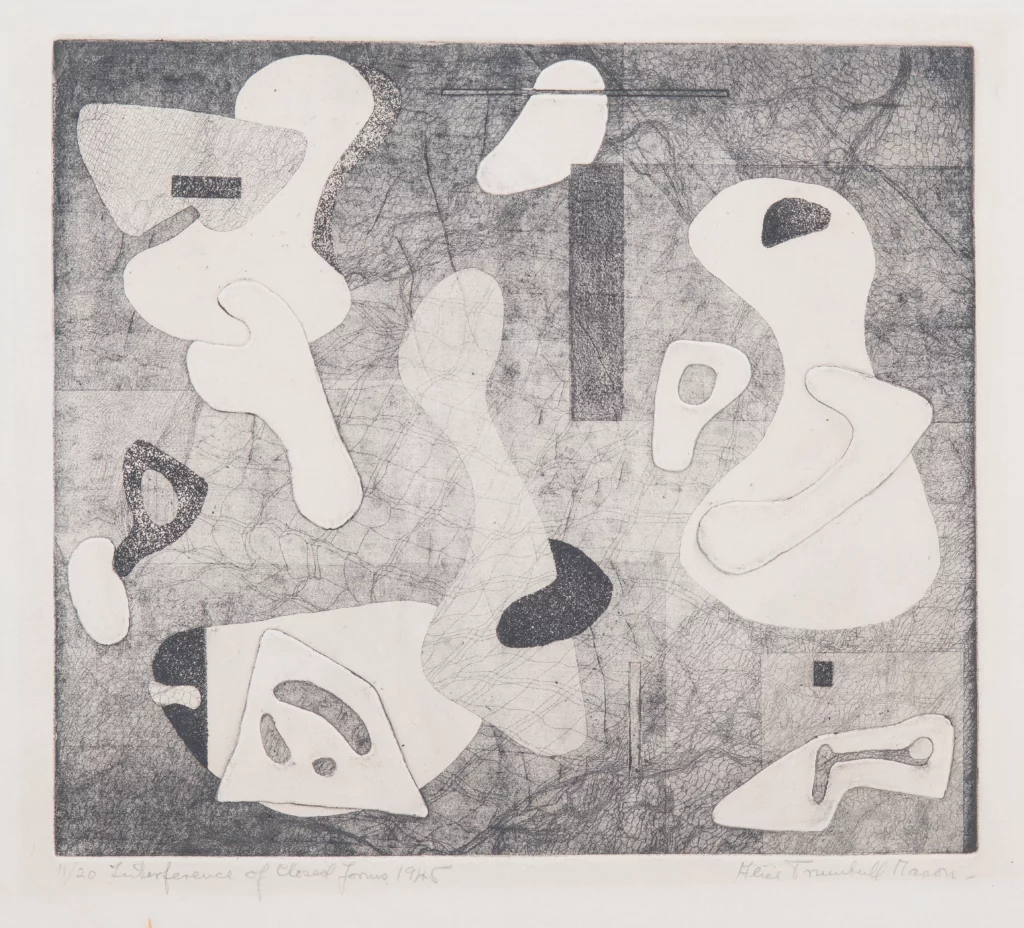

Mason receives the Charles M. Lea prize from the Print Club of Philadelphia for her soft-ground etching Interference of Closed Forms (1945).

Warwood is very supportive of her “headway in art.” She shares her studio with sculptors Dusty (a nickname) and Frances Weiss.

1947

Una Johnson, curator of the department of prints and drawings at the Brooklyn Museum, visits Mason’s studio and sees a mural by Joan Miró, who worked on a commission for the Terrace Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati in the studio adjacent to Mason’s.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum acquires the painting Classic Noctuber (1946).

The Guggenheim Foundation exhibits one of Mason’s paintings in a group show of non-objective American artists at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in Paris. The show tours from 1947 to 1948, traveling as far as Switzerland and Germany.

Her painting Bearings in Transition (1947) is included in the Fifty-eighth Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (November 6, 1947 to January 11, 1948).

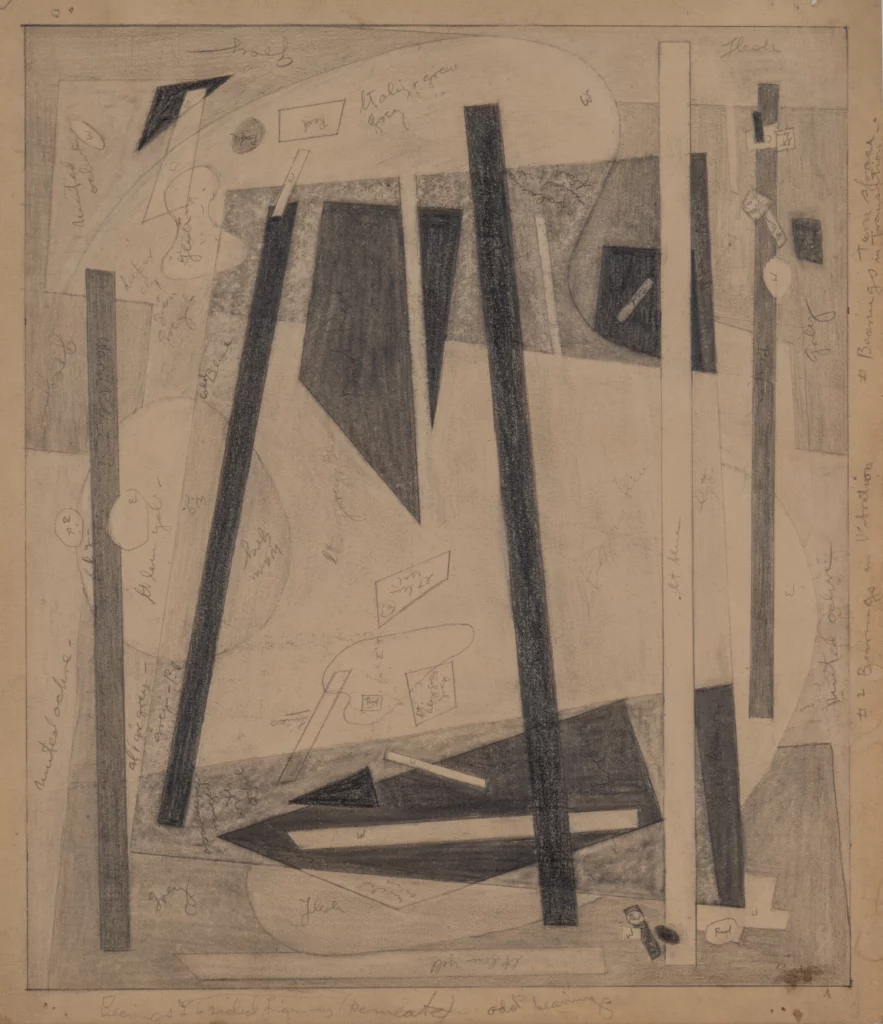

1948

Mason has a solo show at the Rose Fried Gallery (Pinacotheca) on East 68th Street from March 1 to March 20.

She receives the Treasurer’s Prize of the Society of American Etchers.

She devotes more time to her studio practice; Gorky visits her studio, as does Bolotowsky, with whom she is in very close communication.

1949

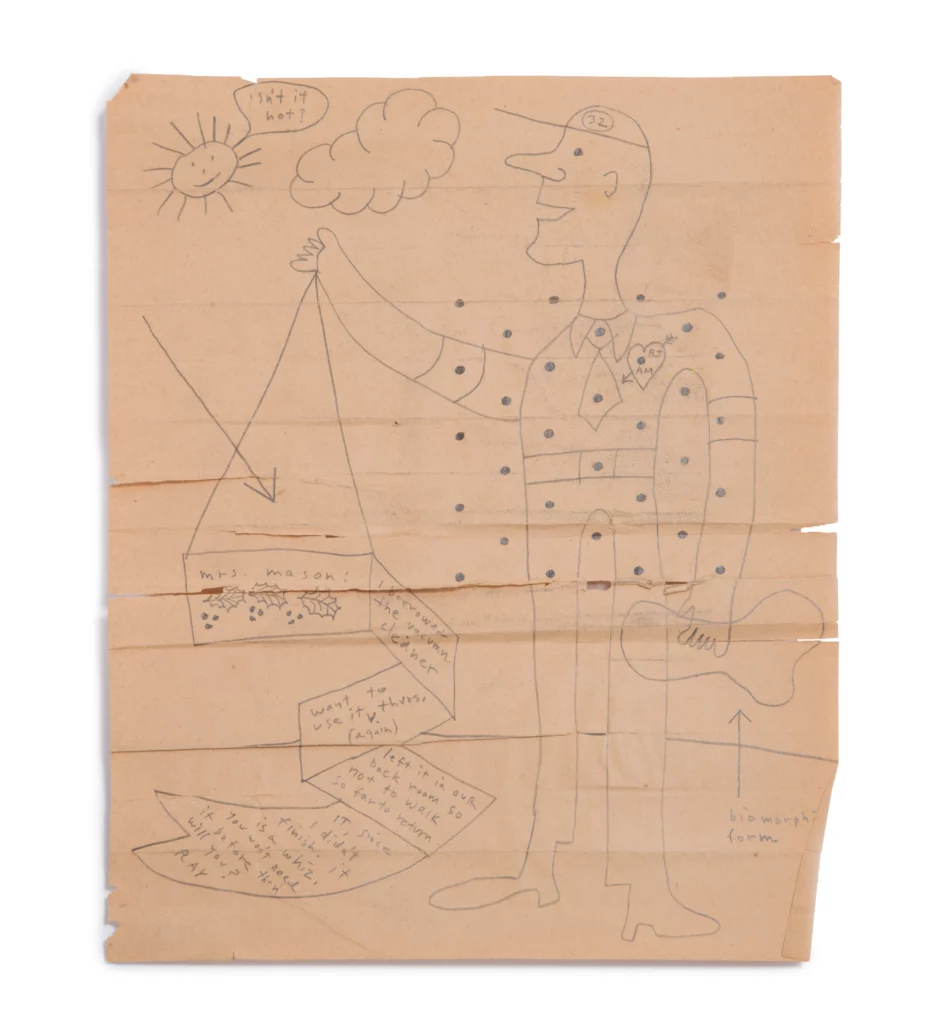

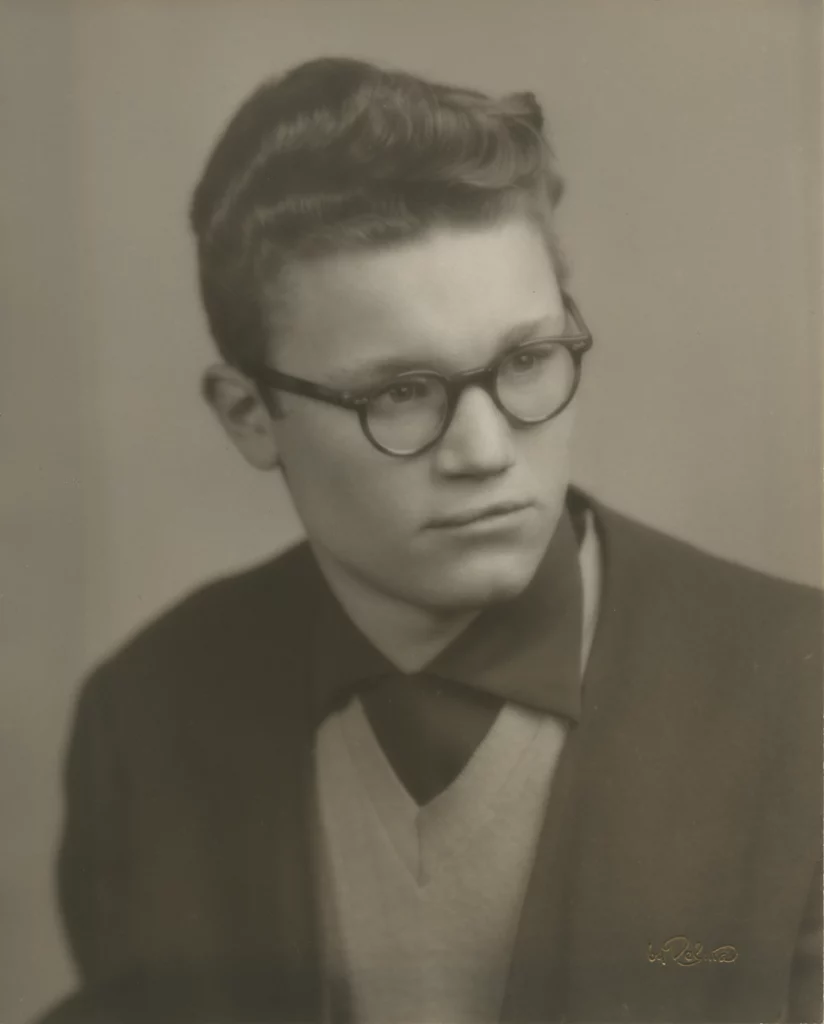

Mason meets Ray Johnson through Richard Lippold. Johnson temporarily uses a studio next to Mason’s, and she often hosts him and Lippold at her apartment for dinner and drinks. In a letter dated October 29, 1950, she describes a scene from one of these dinners: “Ray and I kept going on and on, and on. Laughing like babies, we all 3 were.” She also becomes friends with John Cage and Merce Cunningham and mentions her excitement over Cage’s latest creations in various letters to her daughter, Emily.

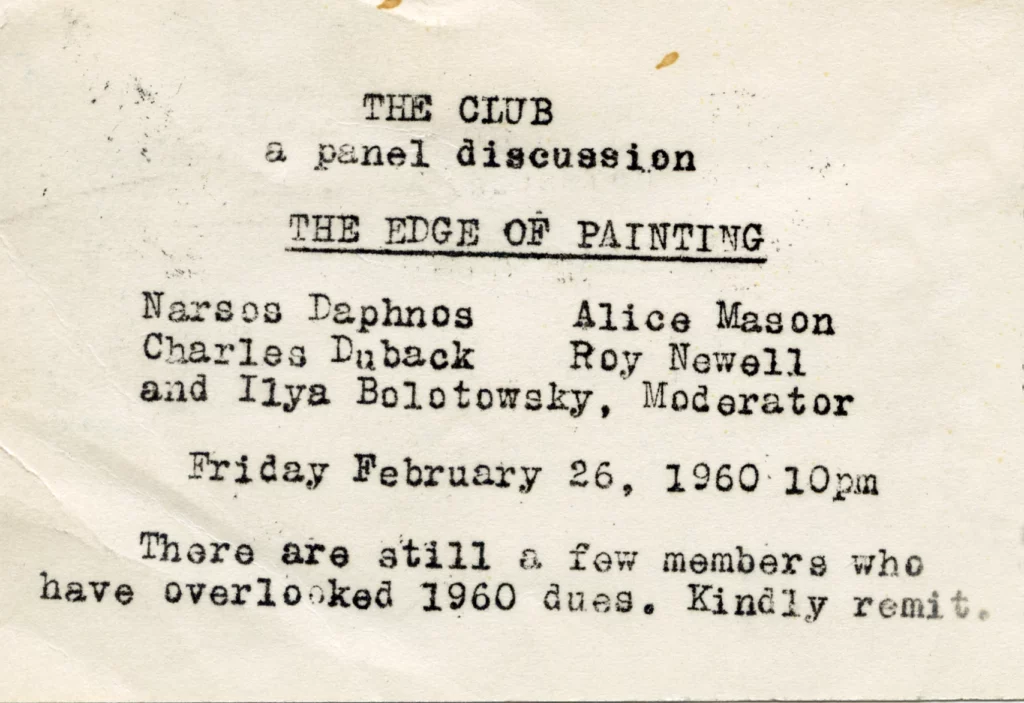

Mason becomes a regular attendee of “The Club,” a loft at 39 East 8th Street in Manhattan, where artists would gather on Friday nights for talks on different topics. The Club was organized by Philip Pavia; other regular attendees included Lassaw, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, and Franz Kline. In his description of one particular evening, Robert Pincus-Witten writes, “Once, in the ’60s, at an evening session of ‘The Club,’ Ad Reinhardt (also a veteran of those early struggles) caught a glimpse of Mason at the edge of the audience. Turning to where he believed she was, he admonished the crowd: ‘Were it not for Alice Trumbull Mason, we would not be here nor in such strength.’ But she had already left the room.”

1950

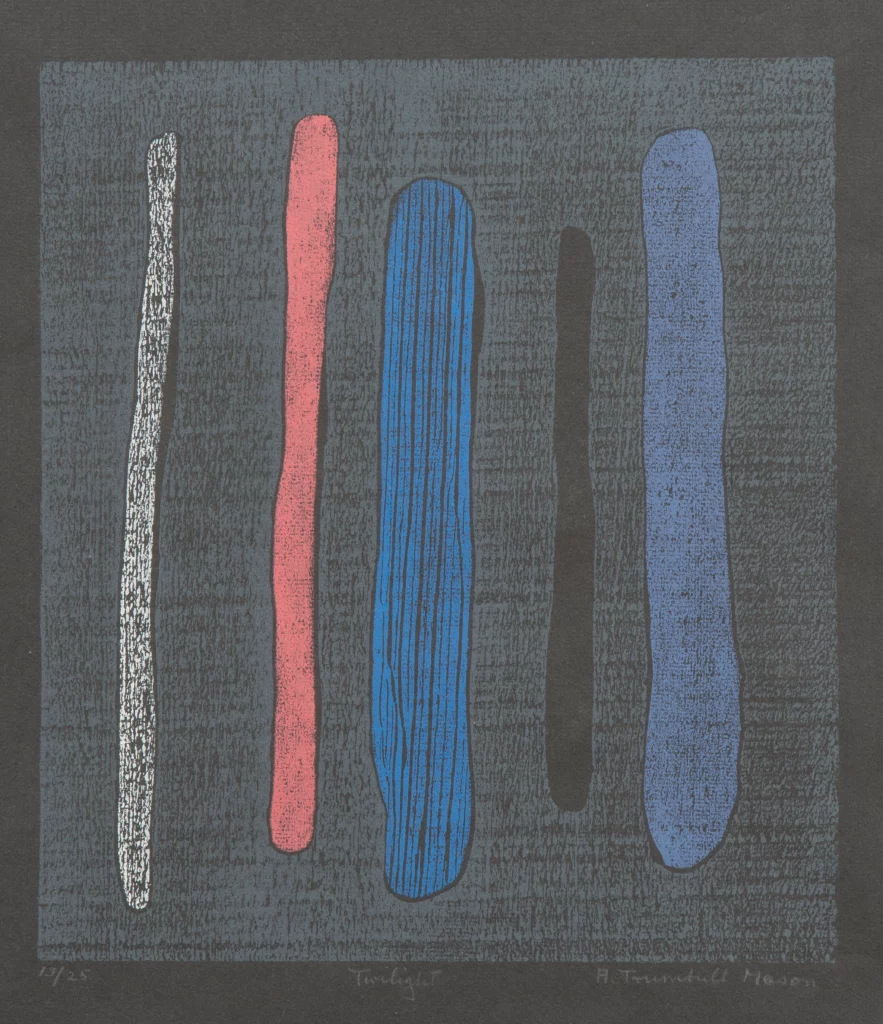

Watching her daughter, Emily, experiment with woodblock prints, Mason expresses her own interest in the medium. She reaches out to Letterio Calapai to borrow his fine press “to have a whack at wood engraving.”

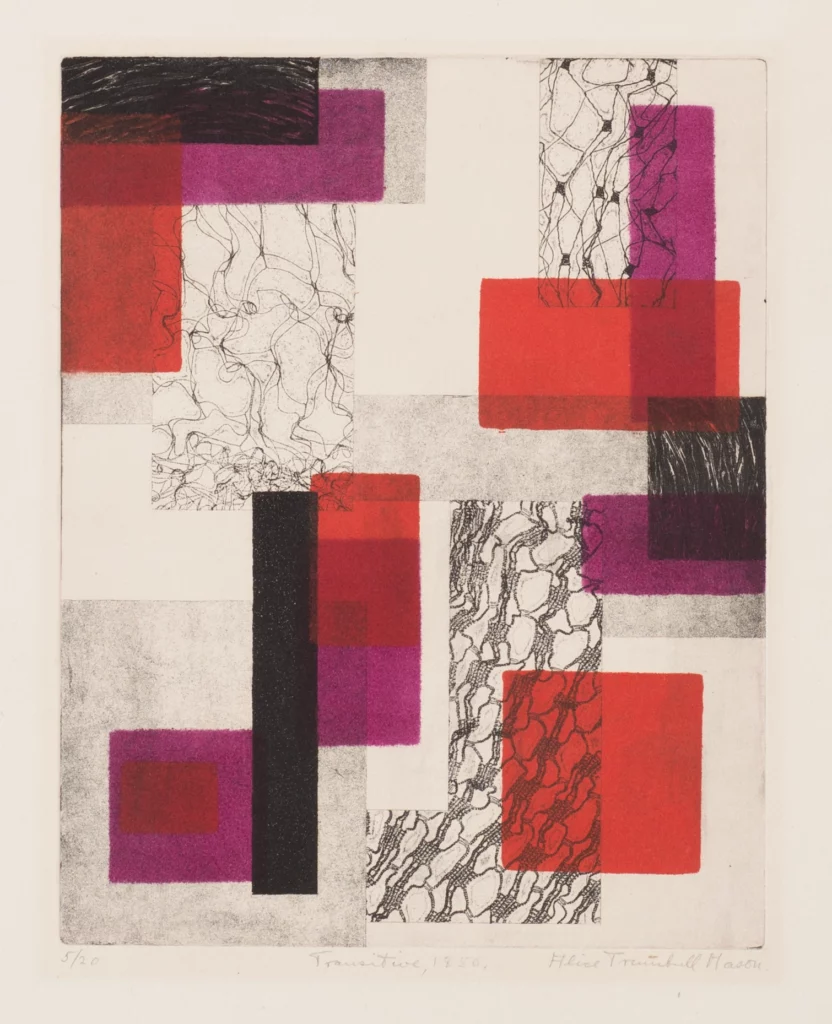

Mason’s 1950s etching Transitive is featured in the AAA show at Rose Fried Gallery.

1951

Mason has a solo show at Rose Fried Gallery on East 68th Street from October through November.

A solo exhibition of her etchings circulates to numerous colleges and university galleries throughout the country.

She shows Magnetic Field (1951) at the Whitney’s Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting (November 8, 1951 to January 6, 1952).

1952

Mason has a solo woodblock print exhibition at Wittenborn and Company in New York.

She receives an award from the Silvermine Guild of Artists of Connecticut in the amount of twenty-five dollars for her painting The Seed is White (1951).

1953-1954

Mason’s painting Staff, Distaff and Rod (1952) is shown in the Younger American Painters exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum, and her painting Slanted Weather (1951) is shown at the 9 Women Painters exhibition at Bennington College in Vermont.

In August 1953 she is invited by Herman More, director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, to submit a painting for the last Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting at the Whitney’s East 8th Street location (October 15 to December 6, 1953). She sends her painting Friendships (1952–1953). She writes in a letter to Emily, “The oil I’m going to send really had no title although the general idea was that of the influence of a group of people or forms modifying each other.”

Mason teaches art to underprivileged children and adolescents at a Police Athletic League center in New York.

1955-1956

Mason participates in the show 14 Painter-Printmakers, curated by Una Johnson at the Brooklyn Museum, on view from November 16, 1955 to January 8, 1956. The museum acquires the woodblock print White Current (1952) and the etching Starry Firmament (1954) for its permanent collection.

She participates in the Whitney Museum’s Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting (November 9, 1955 to January 8, 1956) with the painting Hurricane House (1955).

Mason and Warwood’s son, Jo, enrolls in a recovery program to overcome the substance addiction he has been suffering since young adulthood. After Jo completes the program, Warwood convinces his son to join the merchant marine to escape the toxic urban environment.

Emily begins a relationship with the artist Wolf Kahn the summer before she moves to Venice, Italy, in fall of 1956, on a Fulbright grant.

Mason visits Wolf Kahn’s New York studio and sees his and Emily’s work hanging side by side. To Emily she writes, “I was so pleased to see that your work held its own so well and that you were a good influence on him.

Mason shows A Street of Many Corners (1954) and The Barberry Hedge (1955) in the Twentieth Annual Exhibition of American Abstract Artists with Painters Eleven of Canada at the Riverside Museum in New York, on view from April to May of 1956.

1957

Mason has a solo show at Firehouse Gallery, Nassau Community College.

Having joined the merchant marine, Jo is on his way to Brussels, Belgium. “Both of you spring from a home that contains lots of happiness and also elements of tragedy,” Mason writes to Emily, in reference to Jo. “I heard tragedy discussed today. In relation to O’Neill, Sophocles, Shakespeare. The reason people choose to read and see Tragedies, is partly because it isn’t sham.”

Mason sees John Cage’s Winter Music performance and is disappointed. “It was tough to take,” she writes to Emily. She also visits the Museum of Modern Art and writes to Emily, “The M. of Mod. A. has some good new acquisitions. I suppose museums like formulating the Public’s taste. Or is it that those who shout enough, (as I know some have done) form the Museum’s taste?”

Emily announces her upcoming marriage to the artist Wolf Kahn. Mason and Warwood at first strongly disapprove. Eventually, she gives her blessing: “Your happiness, my sweetheart, is what I want most in the world. Except NO BABY SITTING.”

Emily and Wolf marry in March at the municipal office in Venice, Italy. Mason sends a marriage announcement to the New York Times for the new couple and is pleased when it gets published.

Mason and Warwood visit Emily and Wolf in Venice at the end of September. During their stay, they are worried that everyone’s letters to Jonathan are being returned to sender. Mason and Warwood try finding their son’s whereabouts using all of their contacts.

1958

In early spring, Jo’s body is found in Puget Sound in Washington state, after he has been missing for five months. Mason and Warwood identify his body using his dental records. The reason for his death is unknown, though the family understands it as a probable death by suicide.

Mason sinks into a severe depression. She suffers from malnutrition, fatigue, and alcoholism. “In spite of my disability, I can paint, can’t write very well,” she writes to Emily. She is hospitalized multiple times and struggles to quit drinking.

Emily remembers taking her mother to Towns Hospital on Central Park West around this time. “It was a drying out place for people who wanted to get sober,” Emily says. One day, the art dealer Richard Bellamy, who was also a patient at the time, received a visit from his girlfriend, who brought an iguana. “All these people who just finished going through the DT’s—who knows what they saw!” Emily recalls. “Suddenly there was this live iguana in front of them and they were freaking out. She (Mason) loved Dick Bellamy! She liked, not the absurd, but the irreverent.”

The 14 Painter-Printmakers show continues to travel and is staged in Paris, multiple cities in the United Kingdom, and in many other locations in Europe.

Mason visits Emily and Wolf in Italy at the end of August and stays through September.

1959

At the instigation of Richard Bellamy, Mason has a solo show at Hansa Gallery on Central Park South near Columbus Circle, from April through May.

The Whitney Museum of American Art acquires her painting Memorial (1958–1959) (dedicated to Jo) and features it in its New Acquisitions exhibition.

In September, Cecily Kahn, Mason’s first granddaughter, is born.

Mason becomes AAA president and serves for the next four years.

1960

In February Mason participates in a panel discussion at The Club titled “The Edge of Painting,” moderated by Ilya Bolotowsky.

She participates in the AAA annual show at Riverside Museum.

1961

Mason shows her work at the twenty-fifth annual AAA show at Lever House and in a group show at Green Gallery.

1962

Mason participates in the twenty-sixth annual AAA show and shows A Street of Many Corners (1954) at Area Gallery.

1963

On the advice of Harold Rosenberg, Mason’s painting Arctic Summer (1956) is awarded the Long View Award in New York.

She participates in group shows with the AAA; Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors at Lever House; National Academy of Design ; Washington Gallery of Modern Art; Whitney Museum of American Art; Saint Louis Art Museum in Missouri; and Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts (now the Columbus Museum of Art) in Ohio.

In December Mason visits Emily and Wolf in Rome. She sends loving letters to Warwood with detailed descriptions of her trip and of Cecily.

1964

In March Mason’s second granddaughter, Melany Kahn, is born in Rome.

Mason participates in the Riverside Museum’s West Side Artists: New York City (September 27 to November 8) with her painting Vertical Strata (1963).

1965

Mason participates in a group show at Green Gallery.

1966

Mason participates in group shows, including the thirtieth annual AAA show at Riverside Museum, the Brooklyn Print Annual, and a show at the Museum of Modern Art.

1967

Mason has a survey of fifty paintings at Fire House Gallery-Stewart Avenue in Garden City, New York.

In August, she attends the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire, for the second time.

In November, she has her final solo exhibition at the XXth Century West Galleries.

1968-1970

In August of 1969, Mason participates in the 30th Annual Exhibition of the American Color Print Society at the Associated American Artists gallery.

She continues to paint in her apartment on the Upper West Side. Her alcoholism has progressed and Warwood takes care of her as much as he is able to. They enjoy taking walks along Riverside Drive and feeding the squirrels. She becomes more reclusive and stops showing her work.

1971

Emily and Wolf take Mason to Vermont for rehabilitation treatment. Once she is out of the facility, Emily recalls, they spend “the most beautiful two weeks in Vermont with the family.”

Mason becomes restless and returns to New York to work in her studio. Warwood is spending the summer in Maine with his sister, Mary McGarvey.

Emily is afraid to let her mother go back to the city because she worries that Mason will drink again. Mason promises not to drink and leaves. On June 28, Mason dies alone in her apartment from complications related to alcoholism.

Emily and Wolf clean out the apartment as much as they can but are forced to leave furniture and books behind. Wolf makes an inventory of her paintings and prints. Emily puts all of Mason’s letters and documents in a wooden trunk that she stores in her own apartment in New York, where they remain untouched until research for the monograph Alice Trumbull Mason: Pioneer of American Abstraction begins in 2013.

1972

After retrieving all of Mason’s paintings from her apartment and from her sister Edith’s basement, Wolf persuades art dealer Joan Washburn to look at Mason’s work. Joan recalls, “Wolf gallantly offered to bring a few paintings from their apartment on 15th Street to our apartment on 17th Street. ‘Just look at them for a while,’ said Wolf. Fortunately I agreed, and Wolf appeared with about five small paintings, which we put on the fireplace mantel and about the living room. After some quiet time alone with the paintings, I succumbed, and the rest is history.”

1973

Mason has her first museum retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Selections from the show travel to the University of Nebraska Art Gallery in Lincoln, Nebraska; the A. B. Closson Gallery in Cincinnati, Ohio; the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Montgomery, Alabama; and the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia.

1974

Washburn Gallery, then located at 820 Madison Avenue, hosts its first Alice Trumbull Mason show. Others will follow over the years.