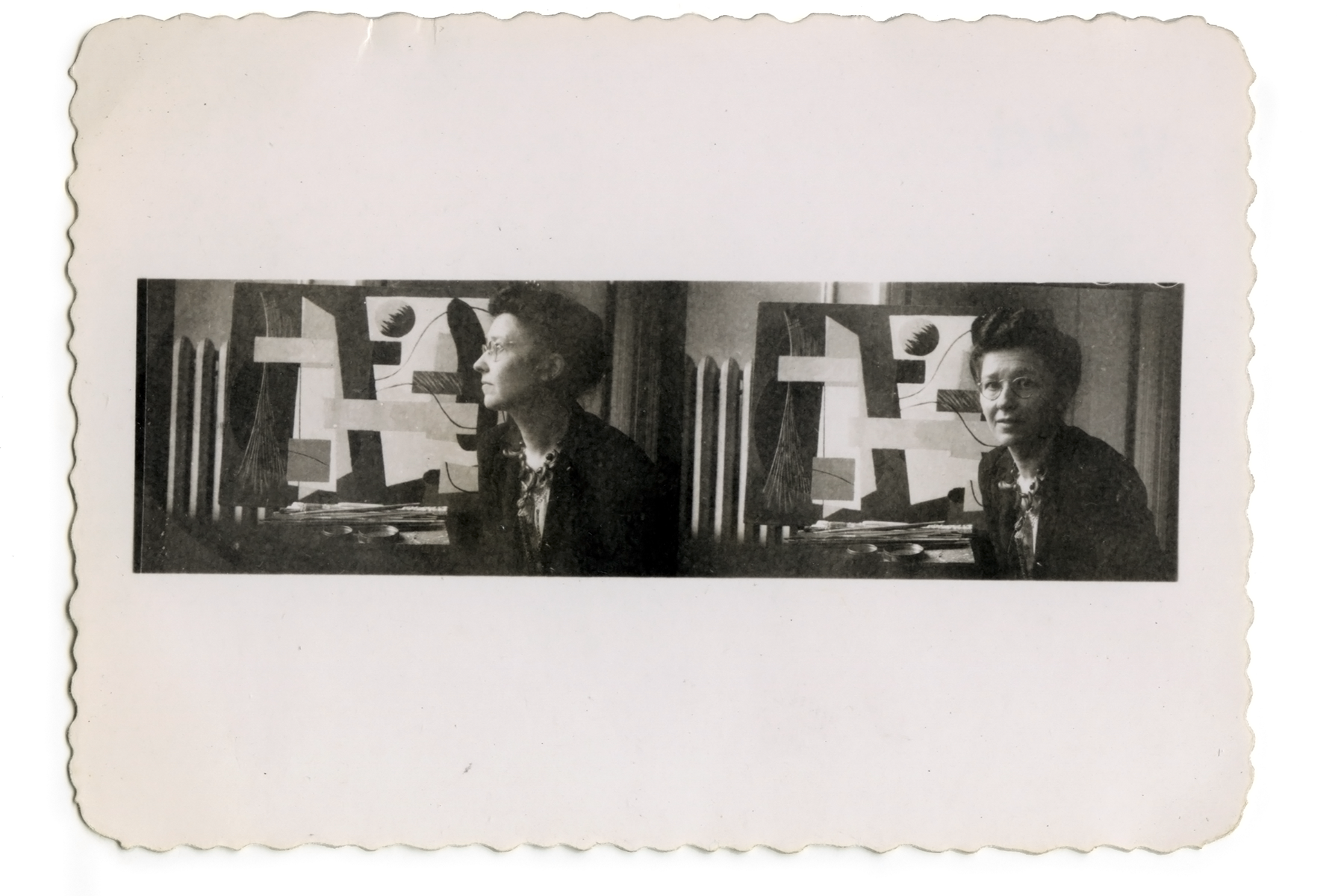

As Ilya Bolotowsky said, “Alice started too early.”

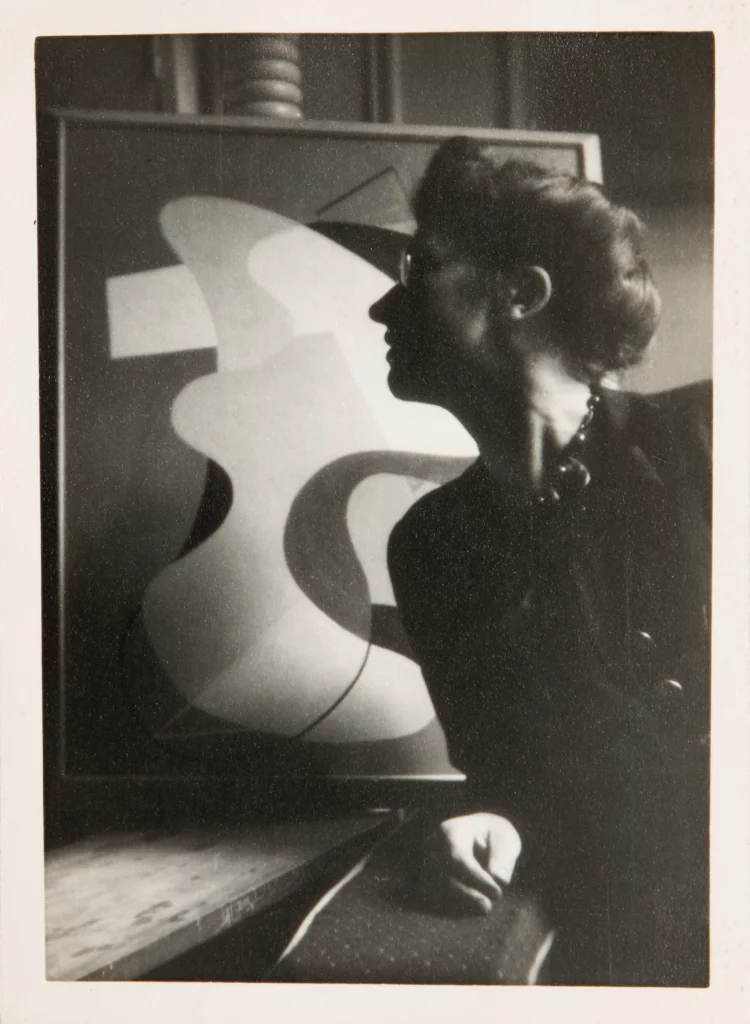

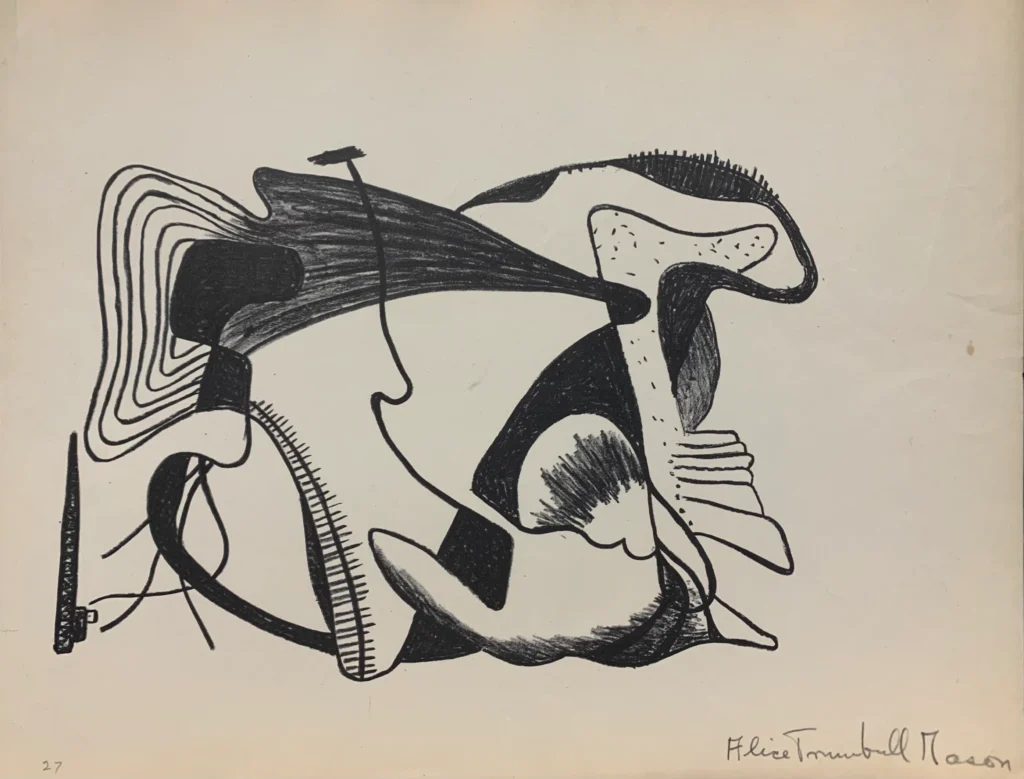

Alice Trumbull Mason was a pioneer on many fronts; not only with abstract painting, but through her unyielding drive to live the life she wanted. Determined, independent, and expressive from a young age, she chose a path which pushed against the gender norms of her time. In closing out Women’s History Month, we’re taking a look at Trumbull Mason’s invaluable contributions to abstract art in the United States.

In the late 1920s/early 1930s, while European Modernism was at a high point, abstract art was considered radical in the United States. In 1965, Trumbull Mason reflected on these years, noting:

“The Museum of Modern Art opened on the 12th floor of the Heckscher Building on Fifth Avenue and for the first time art students were able to see the works of Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso, and Miró here in New York. That was in 1928 or ’29. It was very stimulating and gave us a lot to think about…the big turning point came on the day, when after happily painting all those realistic things, I said to myself: what do I really know? I knew the shape of my canvas and the use of my colors and that I was completely joyful not to be governed by representing things anymore.”

On September 22, 1935, she participated in the Washington Square Art Show, where she was the only artist of over 400 to display abstract work. During this exhibition, she met the abstract sculptor Ibram Lassaw. Soon after, Trumbull Mason, Lassaw, and others begin to hold meetings that would give rise to the group American Abstract Artists (AAA).

Seen as outliers in the art world, the AAA became an official organization in 1936. Many women were involved in the operations of the AAA, such as Trumbull Mason’s friend and fellow artist, Esphyr Slobodkina. Advocating for American abstraction and its visibility and inclusion in museums was a cornerstone of the organization’s mission. In an interview with Ruth Gurin in 1969, Trumbull Mason recounted their protest at MoMA in 1940:

“When we first began forming the American Abstract Artists we said, ‘what is the Museum of Modern Art anyway if it isn’t for abstract artists?’” And we picketed them!”

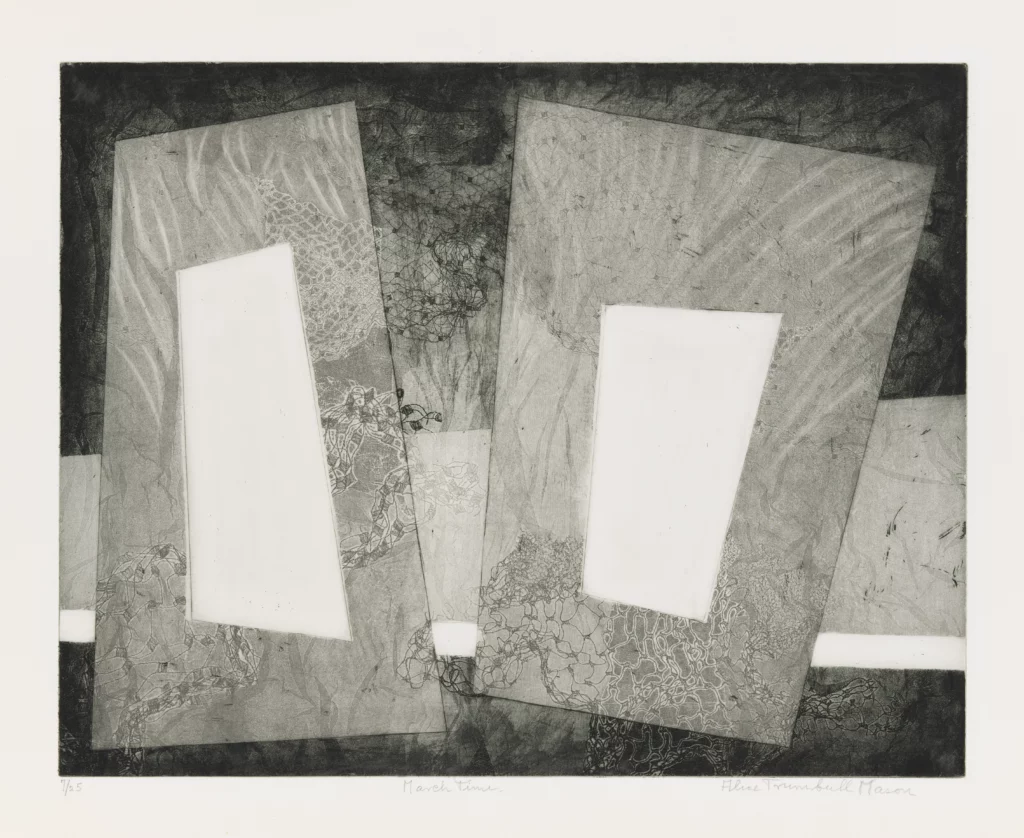

Trumbull Mason continued to advocate passionately throughout her entire career for spaces which fostered artistic community. In 1945, she joined Atelier 17, located at 41 East Eighth Street. Established in the 1920s, artist Stanley William Hayter relocated the studio from Paris to NYC in 1940 due to WWII.

Atelier 17 was well-known among artists in the avant-garde New York art scene, attracting the likes of Anne Ryan, Louise Bourgeois, and Miriam Schapiro. Members of the workshop learned a myriad of printmaking techniques including soft ground etching, engraving, and aquatint, and provided space in which artists could learn, experiment, and exchange ideas in printmaking; particularly, among women.

As Christina Weyl notes in the online project “The Women of Atelier 17: The Biographical Supplement”:

“…the experience of working at Atelier 17 also catalyzed a range of proto-feminist strategies and activity in the decades before women’s art movement of the 1970s. Even if these artists were not self-professed “feminists”—and few identified this way—the studio generated a wide spectrum of proto-feminist attitudes and practices, such as collaboration, network building, and collegial support of one another’s careers.”

© 2025 Emily Mason | Alice Trumbull Mason Foundation/ARS.